RESEARCH

Conflict-related sexual violence

Sexual Violence and Armed Conflict (SVAC)

|

The Sexual Violence and Armed Conflict dataset is the most comprehensive and widely used global data on sexual violence in war. It has recently been updated, and now covers all armed conflicts in the time period 1989-2019.

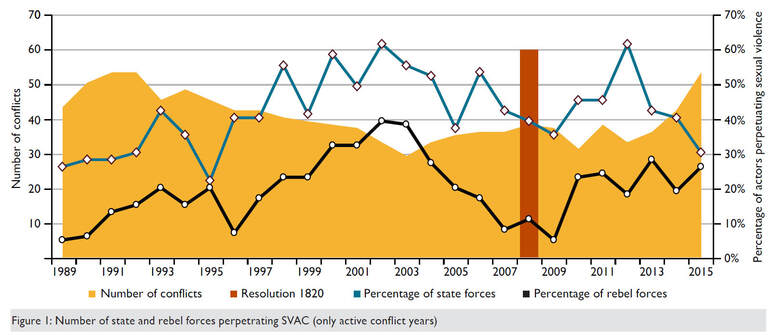

In 2023, the SVAC dataset received the J. David Singer Award for Data Innovation. The award is given by the Conflict Processes Section of the American Political Science Association (APSA). The dataset, coded from the three most widely used sources in the quantitative human rights literature, has as the unit of observation the conflict-actor-year, allowing for detailed analysis of the patterns of perpetration of sexual violence for each conflict actor. The dataset captures six dimensions of sexual violence: prevalence, perpetrators, victims, forms, location, and timing. In addition to active conflict-years, the dataset also includes reports of sexual violence committed by conflict actors in the five years post-conflict. The data documents that the prevalence of sexual violence varies dramatically by perpetrator group, suggesting that sexual violations are common – but not ubiquitous. In addition, we find that state militaries are more likely to be reported as perpetrators of sexual violence than either rebel groups or militias. Finally, reports of sexual violence continue into the post-conflict period, sometimes at very high levels. The data may be helpful both to scholars and policymakers for better understanding the patterns of sexual violence, its causes, and its consequences.

| |||||

Female Empowerment

As part of my work on consequences of sexual violence, I have conducted research in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. I this work, I have focused on sexual violence survivors, their communities, and what support programs can do to empower women. The research included original surveys as well as qualitative research using focus groups. This work was done in collaboration with researchers at the International Center for Advanced Research and Training (ICART) in Bukavu, and Dr. Denis Mukwege.

Climate change and conflictI was central to establishing a systematic empirical literature on climate change and conflict. When I started to work on this topic there was significant attention to potential security implications of climate change, but very little systematic work existed.

To establish a research agenda, Nils Petter Gleditsch and evaluated existing arguments about the link between climate change and conflict and put together the first special issue on the topic in a major academic journal (Political Geography).[i] Our introductory article in the special issue proposed a focus on contingencies that could make climate change relevant for conflict. We also proposed ways to develop more rigorous tests of existing arguments by developing stronger research designs as well as collecting more disaggregated and systematic data. Since this initial work was published in 2007, research on climate change and conflict has grown exponentially, and this article remains one of the most highly cited within this research area. We also published several other articles and book chapters on this topics in the years that followed. [i] Gleditsch, NP & R Nordås 2007. Climate Change and Conflict. Political Geography 26(6): 627–38. |

Group identity and demography

|

I am interested in group identity and demography as it relates to conflict and repression.

Currently, this research has received funding from Minerva, in a collaborative project led by Arun Agrawal. Minerva Research Initiative: 2023-2027 “Climate Change, Demographic Shifts, and Socio-Political Stability in Sub-Saharan Africa” (with Arun Agrawal, Ken Kollman, Yuri Zhukov, Anne Pitcher, H. V. Jagadish) My research on group identity and demography to date has contributed conceptually, theoretically and methodologically to advancing research on group identity, demography, and conflict in ways that moved away from basic structural arguments. For example, it had generally been unclear how ethnic and religious diversity influenced conflict, yielding mixed results from measure of heterogeneity at the country level. I viewed the problem here as being both theoretical and operational. In one study, we conducted in the first ever analysis of inequality within and across sub-national regions.[i] Regions are relevant as they often serve as a proxy for ethnic groups, but they are also made salient by institutions, resource distribution, and state patronage that develops and/or reinforces group identity along regional boundaries. To complete geographically disaggregated analyses, this article produced new regional inequality measures by using Demographic Health Surveys, and found that regional inequality matters of civil conflict. The study was an important early contribution to the literature taking a disaggregated approach to studying conflict processes. Another reason that demographic measures of cultural diversity do not seem like robust predictors of conflict is that most studies fail to account for what contextual factors make identity cleavages salient, such as policies of exclusion and state repression.[ii] In particular, I argued that preemptive repression against demographically expanding minorities perceived as threatening to incumbent regimes, can build cohesion in the minority that is being repressed and trigger counter-reactions, which can escalate to civil war. Youth bulges Building on my interest in repression and when and how demography becomes salient, I have explored the role that youth bulges (typically conceived of as large cohorts of 15-24 year olds) play in prompting state repression. I published an article co-authored with Christian Davenport in American Journal of Political Science which explored this topic.[iii] Up until this point, the literature on state repression had largely considered states to be acting in response to manifest threats with repression. We were the first to explicitly argue that states perceive of future threats and repress preemptively. We proposed that youth bulges are perceived by states as a predictable threat. This makes states with youthful populations likely to preempt instability by increasing repression, even in the absence of behavioral challenges. In a global analysis of all countries from 1976-2000 using the Political Terror Scale, we found strong support for this argument. [i] Østby, G; R Nordås & JK Rød 2009. Regional Inequalities and Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Studies Quarterly 53: 301–324. [ii] Nordås, R. 2012. The Devil in the Demography? Religion, Identity and War in Cote d’Ivoire. In Goldstone, Kaufmann & Toft. Political Demography: How Population Changes Are Reshaping International Security and National Politics. Oxford University Press. Nordås, R. 2014. Religious demography and conflict: Lessons from Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. International Area Studies Review 17(2): 146-66. [iii] Nordås, R & C Davenport 2013. ’Fight the Youth’: Youth Bulges and State Repression. American Journal of Political Science 57(4): 926-940. |

DIVIDENDS, 2021-2025In the fall of 2021, I will be launching a new multiyear project with several collaborators titled From Curse to Demographic Dividends: Sub-Saharan Africa’s Youth Bulges.

This project, funded by the Norwegian Research Council, responds to a general need for understanding why some countries follow a positive and some a negative trajectory when faced with a youth bulge, and to understand the gender dimensions of these processes. We focus more specifically on how to harness the potential for demographic dividends in Sub-Saharan Africa, where demographic youth bulges are most common. In this project, we conceptualize demographic dividends more broadly than has previously been done. Specifically, our analyses will seek to identify conditions, policies, and investments that can produce favorable conditions in youth bulge countries – not only for economic growth, but also political dividends (more vibrant and inclusive political participation) and social dividends (inclusive norms and attitudes) and how these might be mutually reinforcing to foster sustainable development and more peaceful societies. To analyze the demographic curse or dividends, we will combine in-depth and comparative analyses of four countries (Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, and Senegal) with cross-national statistical analyses. |